Call for Sherlock Holmes of course! In the course of a Christmas writing challenge on www.holmesian.net in 2010 I came up with a short piece entitled 'Henrietta's Problem'. It was recieved quite well and when the 2nd Edition of 'Sherlock Holmes and the Lyme Regis Horror' was published by MX Publishing in late 2011, I added the story to the expanded content. A fair few reviews of the book singled out 'Henrietta's Problem' for praise and when I re-read it, I was struck by the thought that it would make a lovely illustrated story for children. Fortunately in Lyme Regis, we have Rikey Austin in out midst, a children's writer and illustrator and she agreed to come in on the project with me and illustrate the now slightly re-written story (originally it was narrated by Watson, but is now narrated by a third party. In a few weeks we will see the fruits of our labours and we are quite excited about the interest already shown it.

Ladies and Gentlemen: I give you, 'Sherlock Holmes and the Missing Snowman...

You can find here news about past, present and future publications, both Sherlock Holmes and non-related Holmes books To follow this year will be, Holmes and Watson: An Evening in Baker Street and The Gondolier and The Russian Countess.

Contents:

What can you find here? Reviews of new and not quite so new Sherlock Holmes novels and collections. Interviews with authors, link to blogs worth following, links to where you can purchase my books and some reviews of my work garnered from Amazon sites. Plus a few scary pics of me and a link to various Lyme Regis videos on YouTube...see what we do here and how....and indeed why!!! Next to the Lyme Regis Video Bar is a Jeremy Brett as Holmes Video Bar and now a Ross K Video Bar. And stories and poems galore in the archives.

Saturday, 29 September 2012

Thursday, 20 September 2012

Justice......Holmes style.

It is axiomatic that whatever the state can do the private sector can do better, and this lesson is rarely illustrated better in literature than in the stories of Sherlock Holmes by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. As it was said by Doyle’s brother-in-law E.W. Hornung, there is no police like Holmes. We have seen a resurgence of interest in the original Sherlock Holmes stories, movies and television programmess. Viewers and fans would do well to note the prevalent anti-state themes that course through these stories like the famous cocaine through the veins of Holmes himself.

The relationship between Holmes and the official London police force showed the marked contrast between a skilled master and a team of public investigators usually barely maintaining the status quo at least a few steps behind the criminals. Scotland Yard reeked of a smug incompetence that amused Holmes, even as he gave them the credit in most cases. They were frequently on the wrong path, lecturing Holmes about him wasting time chasing his fancy theories which ended up being correct. While Inspector Lestrade and the rest were so easily duped by the scheming criminals, Holmes did what the police should have done, what they were getting paid tax payer money to do. In “The Case of the Red Circle” we even see that a constable on duty at a murder scene is easily manipulated by a housewife. Like so many other instances in real life, the private market yielded results where the public option brought errors, gridlock and confusion.

Holmes was a private consulting detective and the antithesis of a police officer, both then and now. His attitude and personality was that of a punk rock, bohemian, displaced country squire with artistic French blood as we learn in “The Case of the Greek Interpreter.”

Holmes’s clients came to him because they had no faith in the official police. They had no confidence in the system so they chose to enlist the services of a private consulting detective, the world’s first as he told Watson (though we do know that Holmes had his free market competitors, his “rivals” as they later came to be known).

Even the British Crown itself at the height of their wealth, power and international prowess sought out Holmes to have him sort out their problems when dealing with spies, thieves and others who had managed to outwit the entire public English establishment.

Indeed, it was Holmes the amateur who was able to, on his own accord, topple the international kingpin of crime Professor James Moriarty, whom the official state police force did not even know existed. But for Holmes, “the work is its own reward,” and accolades from the government meant little to him. We know that in, “The Adventure of the Three Garridebs” Holmes was offered a knighthood and refused it.

As one who strove for justice and peace, Holmes never let the state define what was right and wrong. He was led by his own inner conscience that was much more in touch with the reality of good and evil than any legislative bureaucrat or law enforcement office who always played by the book that the state itself wrote. Though he felt no greater joy than when triumphing over a wicked criminal, he also took the time to free those whom posed no threat to society, regardless of what the state would dictate. As Holmes reminds us in “The Adventures of the Three Gables” he represented not the law but justice.

Holmes let go numerous “criminals” because the state’s bureaucratic automatic policy of incarceration and punishment was antithetical to his vision of justice. For example we can look to Holmes freeing the killer Dr. Leon Sterndale from, “The Devil’s Foot” as he reminds Watson that he acts independently from the police, and that their punishments are not his own. Holmes also refuses to prosecute a killer in “The Boscombe Valley Mystery” because of the circumstances of the attack and the old age of the killer. In “The Adventure of Charles Augustus Milverton” Holmes lets a killer go free because of who the deceased was and the ways in which he had tormented his eventual killer. In “The Crooked Man” he releases a con artist on the grounds that he get a respectable job and scheme no more. We also see Holmes release the perpetrators in “The Adventure of the Priory School,” “The Adventure of the Three Gables,” “The Adventure of the Sussex Vampire,” “The Adventure of the Second Stain” and “The Adventure of the Veiled Lodger.” Holmes did not think that he was the law or above the law, he simply defined and pursued law and justice apart from the definitions and directives of the state.

A great example of this is when Holmes also frees the thief James Ryder in the Christmas tale “The Adventure of Blue Carbuncle.” After Ryder begs Holmes for mercy, Holmes allows him to go free. Holmes then waxes eloquently on what has transpired, showing a remarkable grasp of the nature of incarceration. He tells how the state’s system that worsens and hardens citizens who have made a solitary and relatively harmless bad choice into career criminals:

'I am not retained by the police to supply their deficiencies. If Horner were in danger it would be another thing; but this fellow will not appear against him, and the case must collapse. I suppose that I am commuting a felony. But it is just possible that I am saving a soul. This fellow will not go wrong again; he is too terribly frightened. Send him to jail now, and you make him a jail-bird for life. Besides, it is the season of forgiveness.'

It is in essence the very credo of Sherlock Holmes and one which endears us to the man.

The relationship between Holmes and the official London police force showed the marked contrast between a skilled master and a team of public investigators usually barely maintaining the status quo at least a few steps behind the criminals. Scotland Yard reeked of a smug incompetence that amused Holmes, even as he gave them the credit in most cases. They were frequently on the wrong path, lecturing Holmes about him wasting time chasing his fancy theories which ended up being correct. While Inspector Lestrade and the rest were so easily duped by the scheming criminals, Holmes did what the police should have done, what they were getting paid tax payer money to do. In “The Case of the Red Circle” we even see that a constable on duty at a murder scene is easily manipulated by a housewife. Like so many other instances in real life, the private market yielded results where the public option brought errors, gridlock and confusion.

Holmes was a private consulting detective and the antithesis of a police officer, both then and now. His attitude and personality was that of a punk rock, bohemian, displaced country squire with artistic French blood as we learn in “The Case of the Greek Interpreter.”

Holmes’s clients came to him because they had no faith in the official police. They had no confidence in the system so they chose to enlist the services of a private consulting detective, the world’s first as he told Watson (though we do know that Holmes had his free market competitors, his “rivals” as they later came to be known).

Even the British Crown itself at the height of their wealth, power and international prowess sought out Holmes to have him sort out their problems when dealing with spies, thieves and others who had managed to outwit the entire public English establishment.

Indeed, it was Holmes the amateur who was able to, on his own accord, topple the international kingpin of crime Professor James Moriarty, whom the official state police force did not even know existed. But for Holmes, “the work is its own reward,” and accolades from the government meant little to him. We know that in, “The Adventure of the Three Garridebs” Holmes was offered a knighthood and refused it.

As one who strove for justice and peace, Holmes never let the state define what was right and wrong. He was led by his own inner conscience that was much more in touch with the reality of good and evil than any legislative bureaucrat or law enforcement office who always played by the book that the state itself wrote. Though he felt no greater joy than when triumphing over a wicked criminal, he also took the time to free those whom posed no threat to society, regardless of what the state would dictate. As Holmes reminds us in “The Adventures of the Three Gables” he represented not the law but justice.

Holmes let go numerous “criminals” because the state’s bureaucratic automatic policy of incarceration and punishment was antithetical to his vision of justice. For example we can look to Holmes freeing the killer Dr. Leon Sterndale from, “The Devil’s Foot” as he reminds Watson that he acts independently from the police, and that their punishments are not his own. Holmes also refuses to prosecute a killer in “The Boscombe Valley Mystery” because of the circumstances of the attack and the old age of the killer. In “The Adventure of Charles Augustus Milverton” Holmes lets a killer go free because of who the deceased was and the ways in which he had tormented his eventual killer. In “The Crooked Man” he releases a con artist on the grounds that he get a respectable job and scheme no more. We also see Holmes release the perpetrators in “The Adventure of the Priory School,” “The Adventure of the Three Gables,” “The Adventure of the Sussex Vampire,” “The Adventure of the Second Stain” and “The Adventure of the Veiled Lodger.” Holmes did not think that he was the law or above the law, he simply defined and pursued law and justice apart from the definitions and directives of the state.

A great example of this is when Holmes also frees the thief James Ryder in the Christmas tale “The Adventure of Blue Carbuncle.” After Ryder begs Holmes for mercy, Holmes allows him to go free. Holmes then waxes eloquently on what has transpired, showing a remarkable grasp of the nature of incarceration. He tells how the state’s system that worsens and hardens citizens who have made a solitary and relatively harmless bad choice into career criminals:

'I am not retained by the police to supply their deficiencies. If Horner were in danger it would be another thing; but this fellow will not appear against him, and the case must collapse. I suppose that I am commuting a felony. But it is just possible that I am saving a soul. This fellow will not go wrong again; he is too terribly frightened. Send him to jail now, and you make him a jail-bird for life. Besides, it is the season of forgiveness.'

It is in essence the very credo of Sherlock Holmes and one which endears us to the man.

Monday, 17 September 2012

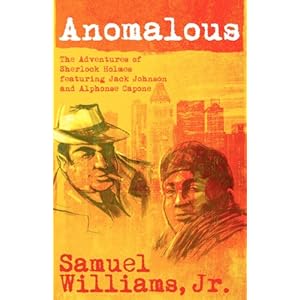

Anomalous.......

Anomalous by Samuel Williams Jr is an engrossing read, pacy, exciting and full of details that add rather than detract from the story and riveting characters such as Jack Johnson the heavyweight boxing champion and a certain Al Capone. The plot itself is involving, well-worked out and always captures both the imagination and attention. The major players are exremely well-portrayed and their dialogue is always, always convincing. A big plus, and it's not always so with pastiches, is how well Samuel captures the characters of Sherlock Holmes and Doctor Watson, the author knows his men, knows his canon and it shows. They are spot on in looks, character and voices, not always an easy thing to achieve by any means. The transition from 1912 America to 1913 England is seamless. Jack Johnson pulled no punches and neither does Samuel Williams Jr.......an inspired debut.

Anomalous by Samuel Williams Jr is an engrossing read, pacy, exciting and full of details that add rather than detract from the story and riveting characters such as Jack Johnson the heavyweight boxing champion and a certain Al Capone. The plot itself is involving, well-worked out and always captures both the imagination and attention. The major players are exremely well-portrayed and their dialogue is always, always convincing. A big plus, and it's not always so with pastiches, is how well Samuel captures the characters of Sherlock Holmes and Doctor Watson, the author knows his men, knows his canon and it shows. They are spot on in looks, character and voices, not always an easy thing to achieve by any means. The transition from 1912 America to 1913 England is seamless. Jack Johnson pulled no punches and neither does Samuel Williams Jr.......an inspired debut.

Anomalous – The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes is available from bookstores including in the USA Barnes and Noble and Amazon, in the UK Waterstones Amazon and Book Depository(free worldwide delivery) and in electronic formats – iTunes(iPad), Kindle, Nook and Kobo.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)